If you’re a North American who isn’t living under a rock you know about #TSE2017—and I could ride my bike there.

If you’re a North American who isn’t living under a rock you know about #TSE2017—and I could ride my bike there.

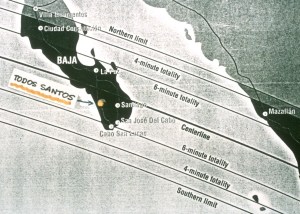

Ha ha! JK. I’m not riding my bike 21 miles. But the edge of totality falls across Redmond, Oregon on August 21, 2017 at the northernmost edge of Roberts Field airport, just up the highway from my home in Bend.

Coincidence? I think not. Even the weak Kallawalla mystic would say it’s predictable that I live in the path of totality, a quarter of a century from experiencing my first total solar eclipse.

People ‘round these parts say they remember the Northwest eclipse of 1979—no they don’t. It was clouded out. (Disagree? Let’s see your corona shot. Yeah, I thought so.)

On eclipse day I will not be driving from my house—gridlock will grip highways 97 and 26 on the weekend before August 21st and traffic to the path from all directions will be slower than the Bend Broadband wireless network.

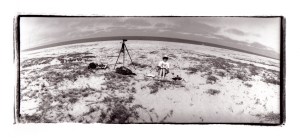

I’ll be at the Oregon Airstream Club Blackout Rally on the shore of Lake Simtustus, the reservoir behind Pelton Dam, in a sea of silver among my fellow Airstreamers.

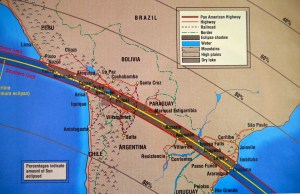

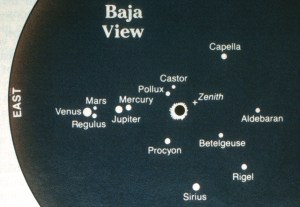

Below: Lake Simtustus site; position of the sun at first contact on August 21; Great American path