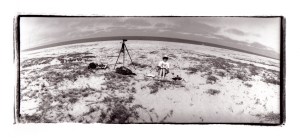

Before totality (viewed from the Bolivian Altiplano, the sunniest location on the eclipse track in 1994) we were taken on a whirlwind tour of, like, the whole country—a basic, barren nation with pockets of jaw dropping scenic and cultural beauty and colorful people. The women dress in native fashions: full pleated skirts and thick shawls with a cholita bowler hat worn rakishly on the head. Luis, one of the guides, explained that Bolivia is “simple and poor”, and because of the climate the residents “crave sugar and pork lard, so all the women are huge,” (his word). To their men, that’s a sign of strength and beauty.

Before totality (viewed from the Bolivian Altiplano, the sunniest location on the eclipse track in 1994) we were taken on a whirlwind tour of, like, the whole country—a basic, barren nation with pockets of jaw dropping scenic and cultural beauty and colorful people. The women dress in native fashions: full pleated skirts and thick shawls with a cholita bowler hat worn rakishly on the head. Luis, one of the guides, explained that Bolivia is “simple and poor”, and because of the climate the residents “crave sugar and pork lard, so all the women are huge,” (his word). To their men, that’s a sign of strength and beauty.

The tour group was put up in a familiar, ultranice Radisson in the big-city capital of La Paz. Throughout the trip Spears Travel made sure we were treated to the very best accommodations Bolivia had to offer. (Read between the lines.) I poked around town, bargaining for alpaca textiles and visiting the spooky witches market to buy lucky totem figures blessed by the brujas with yarn.

I climbed off a bus (after a ride so bumpy that water splashed out of a half-full Nalgene bottle) to explore the ruins at Tiwanaku and stand before the stone Gate of the Sun, believed to be an ancient observatory.

I watched my tour mates heaving over the rail of the hydrofoil jet boat that flew across Lake Titicaca on the way to the fountain of youth on the sacred Isla del Sol. At the car cha’lla blessing at Dark Virgin of Copacabana shrine, vehicles decorated with red, yellow and green flowers—the colors of the Bolivian flag—waited in rows for the priest to sprinkle them with holy water. Beer, champagne and colas were also on hand to acknowledge the earth goddess, Pachamama. (Bolivians believe that our planet is a being to share with and thank—and when you have a drink, you pour a splash on the ground for Mother Earth.) Afterwards, I took part in a little sacred ceremony—a sort of baptism by flowers dipped in the water of Lake Titicaca—and was ordered to repeat, “I will not lie, I will not steal, I will not be lazy,” (the three worst Incan sins). A pisca and gingerale toast sealed the oath.

I had my fortune told by a Kallawalla mystic using “guinea pig x-ray” magic, with dubious results. We gathered in a dark tent late at night; a wizened nut-brown gentleman in robes sat cross-legged in the center. “Who has a question or concern for the mystic?” announced the guide. Of course no one stepped up, so I took one for the team and raised my hand. I was escorted to a place on the ground before the seer and quietly posed a question about my work (how 90s was that). The mystic ruminated and finally said through an interpreter, “you are very worried, but everything will be okay.” The next person stepped up and asked their question. The answer? “You are very worried, but everything will be okay.” Ha! And so on, to everyone.

In Potosi, the worlds highest city, I went into a catacomb piled high with the skulls and bones of the faithful. I saw wild vicuña and flamingoes on the plains. I visited a cemetery by myself on All Souls Day and walked among families restoring the above-ground grave dioramas, strumming guitars and placing flowers for the spirits to enjoy. (“Were the dead grateful?” asked David, the videographer in our group. “I’m sure they were,” I stupidly answered. I got the joke about five minutes later.)

It was an honor to be in the presence of the late Ken Willcox, eclipse coordinator on the tour. Ken made it his business to circulate through our train to the eclipse viewing area and collect small items and anything that we could offer as a school supply—paper, pens, pencils, decks of cards—and distribute them to the children who came running when we stopped on the tracks in the poor villages.

By our final destination in the town of Sucre, the nerds looked less nerdy. Those once pasty and dandruffy and afflicted with altitude sickness at the beginning of the tour were now stronger, buoyant. The men became vital and scruffy, wearing Indiana Jones-style fedoras they found in a market somewhere. Faces were tanned and spirits were high as the travelers joyfully licked ice cream cones while sauntering around Plaza 25 de Mayo square. That night, all enjoyed a fancy farewell dinner, served in a Euro-style restaurant with white linen tablecloths.

Was it the asparagus with cream sauce served at dinner? The ice cream in the square? (Probably not the ubiquitous pollo and jojos, served piping hot from street vendors.) Whatever it was, I would learn that anyone who wasn’t flattened by altitude sickness at the beginning of the journey later contracted a frightening intestinal illness. One unfortunate dude hosted an amoeba so debilitating that he had to be a Boy in a Bubble and underwent a complete immune replacement—a process that took a year from his life.

I fell viciously and unexpectedly ill with dysentery on the flight home. The airline crew allowed me to lay on the floor of the bathroom during the last hour of the flight including WHILE THE PLANE LANDED. I was removed from the airport in a wheelchair, and was bedridden and delirious for two solid weeks.

It was worth it.

Above: Chasers at the mint

Below:

(Photography in Bolivia was difficult in 1994; it was generally verboten to take a picture of anything living, not just people and animals. A photo of a potato would take its soul, too—the next day it would surely be rotten inside. I couldn’t resist selfishly capturing certain memories for myself while trying to keep a respectful distance, and I still got in trouble. Once, three teenage girls in yellow and white school uniforms were sitting beneath a statue at the end of a town square; a breathtaking photo opp. They saw me trying to sneak a long shot from the other end of the square—from all that distance away!—and ran. When I put my camera away, they returned. Lesson learned.)

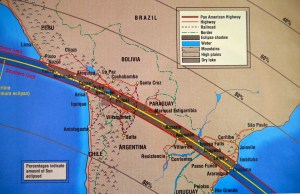

Path of totality 1994

Lake Titicaca

Bonafied by King Manco Kapac

City scenes

Above-ground cemetery tombs

Remote village

Ken and the kids

Boliviano converter

Shop lady

Witches market

Cerveza nacional

Climbing toward the Altiplano

(Do you see yourself in these or any photos on this website? I’d love to hear from you.)