It was a wedding gift of sorts. Two months after we married, Ralph sent me on my own to join another TravelQuest eclipse tour, this time on the glamorous expedition ship Orion. The dream itinerary: a private charter flight from Cairns Australia to Papua New Guinea to join the Orion for nine days—a ship small enough to carry passengers to several remote villages—and a grand finale, totality at the Great Barrier Reef.

It was a wedding gift of sorts. Two months after we married, Ralph sent me on my own to join another TravelQuest eclipse tour, this time on the glamorous expedition ship Orion. The dream itinerary: a private charter flight from Cairns Australia to Papua New Guinea to join the Orion for nine days—a ship small enough to carry passengers to several remote villages—and a grand finale, totality at the Great Barrier Reef.

The intimate Orion (90 passengers, 75 crew) came equipped with kayaks, Zodiac landing craft (many of our ports were “wet landings”), and diving and snorkeling gear. The professional expedition staff included a marine biologist, acclaimed wildlife photographer Sue Flood, a field biologist, meteorologist Jay Anderson, planetary scientist and former NASA astronaut Thomas Jones, and a cultural anthropologist—an Aussie who married into a PNG village and actually became a chief, who knew everyone and all the local customs.

Each day at sea there were workshops and lectures on the flora and fauna of PNG, space travel, photography, and a cultural briefing on the islands we would visit—all accompanied with drinks and traypass hors d’oevres. The food—three squares a day plus high tea and assorted cocktail parties—was exquisitely prepared and, like most cruises, nonstop. I was giddy like a girl asked to the prom when a note addressed to Miss Coleman in Stateroom 310 included an invitation to dine that night at the table of Captain Andrey Domanin, “Master of the Orion”.

One night after dinner the captain took a joy ride past the actively-erupting Manam volcano; red lava flowed down the side and rocks and flames shot out of the top. (As I watched from the deck, a glass of champagne in my hand, I wondered: am I asleep?)

Performers boarded the Orion in our last island port and drummed a farewell before we sailed to the Great Barrier Reef. The last days at sea were rough, literally and figuratively. Barf bags were tucked behind the rail on every deck. The ship’s doctor Doctor Chris administered shots and big blue nausea pills; Dramamine was heaped in a tasteful bowl on the reception counter.

I was one of the few unaffected and had work to do—an article on Burning Man due for Trailer Life magazine. I found an empty bar on the top floor of the ship but my laptop kept sliding off the table what with all the pitching and yawing. (Cruise ship tip: when seas are high, climb down to the level nearest the hull, where it’s calmer.) The dining room was sparsely populated with wan-looking, uncommunicative passengers. The ill-conceived cocktail of the day was banana liqueur and coconut rum—a little warm ginger ale might have been a bigger seller.

(Sound like fun anyway? Get on board for this one: the TravelQuest South Pacific Cruise to totality on the Paul Gauguin with a pre-vacay on Easter Island.)

Above: The Orion

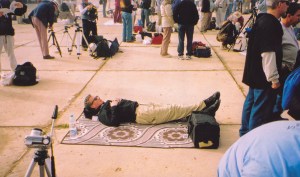

Below:

Commemorative rubber stamps; All aboard; Lounge and meeting room; Stateroom 310; Cairns; Snorkel gear; On deck; From the Zodiak; Manam volcano; What to wear?; Dancers on board; Still waiting for the Green Flash.

Find more photos here

Like most island nations in the tropical Pacific, chewing betel nut is a popular pastime among the people of Papua New Guinea. The effect (I’m told) is a mild and calming buzz, akin to cigarette smoking. Like cigarettes, betel nut is addictive and not without side effects beyond the ghastly red smile: gum disease, tooth loss, and mouth cancer.

Like most island nations in the tropical Pacific, chewing betel nut is a popular pastime among the people of Papua New Guinea. The effect (I’m told) is a mild and calming buzz, akin to cigarette smoking. Like cigarettes, betel nut is addictive and not without side effects beyond the ghastly red smile: gum disease, tooth loss, and mouth cancer.