To be accurate, 15,702 feet; a private train took us to view totality on the Altiplano along the Rio Mulatos-Potosi railway line, the world’s ninth highest.

To be accurate, 15,702 feet; a private train took us to view totality on the Altiplano along the Rio Mulatos-Potosi railway line, the world’s ninth highest.

The train was beyond rustic. Eight hours of squeaking metal, with hard seats in cold and cramped compartments. To get to the dining car (for yet another meal of pollo and fries) we had to take a giant step between the cars, the rushing tracks visible in the yawning, swaying crack below.

We boarded the evening before the eclipse and the train clattered through towns and remote villages for hours, higher and higher into the night. We handed our freebie paper eclipse shades and filters out to villagers when the train stopped. We moved through a huge All Souls Day celebration with covered tents and couples dancing, bands playing caporal and cumbia music, people holding up their beers to toast us as we pass.

All the trains to the centerline were coordinated from below and embarked from the station two miles apart, and the nighttime passage and early arrival time ensured that no smoke, light or vibration would pollute the eclipse viewing areas.

The train screeched to a stop at 4 a.m. where the weather satellite said to, somewhere outside Sevaroyo. With the trains filled with groggy travelers suddenly silently in place, it was hushed and dark and cold before dawn on eclipse morning.

No flashlights or flash photography were allowed. We were advised to dress in warm layers—there would be no heat, no generator—and prepare to be on camera: an accompanying film crew hired by National Geographic was about to go to work.

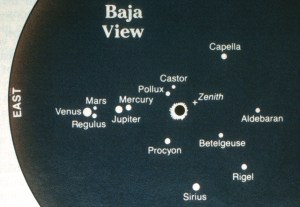

After a hurried breakfast we all piled out onto the dark desert with our scopes and cameras; we were late arriving, and there wasn’t much time for observing before sunrise at 6:30. I saw Crux, the Southern Cross for the first time—a stargazer’s milestone and proof that a North American traveler is very far from home.

I was excited to be observing at a high-altitude site—about as far from my sea level first eclipse as possible—where the coronal streamers were expected to be long and bright (as light from the corona wouldn’t be dulled by Earth’s atmosphere). The air was thin and the wind was chilly. Local children, families, and military guards armed with machine guns materialized to view partiality through our solar scopes and eclipse glasses. I later learned that only 600 souls were present on the Altiplano.

The short three-minute totality began at 8:22 a.m. at 35.80 degrees above horizon. As predicted, the delicate corona was detailed and luminous. I got a good look at Baily’s Beads (for those who don’t know, these are the dots of light in a ring formed by SUNLIGHT SHINING THROUGH THE MOUNTAINS ON THE MOON, sorry, I can hardly fathom it), and this time, both diamond rings.

Above: Sunrise on the Altiplano

Below:

Boarding the ENFE train

Viewing site

Locals and travelers witness together

Group shot at the train