Summer, 2019. I attempted my eighth total solar eclipse—my third one at sea. (November 2012 I watched from the deck of the expedition ship Orion in the Great Barrier Reef. The February ’98 totality was actually viewed from the beach on Aruba; about half the eclipse group aboard the Carnival Fascination opted for luck on land, while the others sailed away in search of clear skies somewhere in the Southern Caribbean Sea.)

Summer, 2019. I attempted my eighth total solar eclipse—my third one at sea. (November 2012 I watched from the deck of the expedition ship Orion in the Great Barrier Reef. The February ’98 totality was actually viewed from the beach on Aruba; about half the eclipse group aboard the Carnival Fascination opted for luck on land, while the others sailed away in search of clear skies somewhere in the Southern Caribbean Sea.)

I was excited to see my eighth TSE, but more excited to finally travel to Easter Island, which hosted her own eclipse in 2010. (All venues were sold out when I tried, very late in the game, to make travel arrangements that year.)

Happy again to be chasing the shadow with TravelQuest International; Aram Kaprielian and his expedition teams are brand consistent in that they always offer the best available accommodations, science experts, local guides, and overall travel experience to bookend the corona, the jewel of the journey. (Hopefully. More on that later.)

Easter Island—Rapa Nui—was nothing like I imagined, and exactly as I imagined. It’s more populated, with a busy “city” center, Hanga Roa. The hotel chosen for the TravelQuest guests, the Hangaroa Eco Village, was far more upscale and comfortable than I could have dreamed. I expected heat and mosquitos—none. But the Moai, those famous Easter Island heads, dotted the deforested landscape in the way they are always pictured. Ancient. Eerie. Confusing. Tikigod-like, without the party vibe. One thousand or so of these statues, heads and squat bodies representing humanoid beings, range between six and 30 feet tall. Their weight is unimaginable; several tons. How on earth were they made? How were they transported? Who are they? WHY are they?

There’s only one flight to and from Tahiti each week, so if you approach Rapa Nui from Faa’a on LATAM (formerly LAN Airlines, based in Santiago, Chile), you’ll have to kill time until you’re returned to Tahiti. There’s plenty to keep a visitor busy on Easter Island without feeling rushed, and in a week you can comfortably see it all.

We saw the sacred site of Tahai: three ceremonial ahus (platforms) with restored Moai, including the only one with his coral eyes reinserted. (On our last evening we watched the sun set behind the Moai of Tahai—where we started on day one—from the hill above. A Polynesian “buried” feast was served, cooked in an earthen (umu) oven, followed by a folkloric performance.

We explored Ahu Tongariki, the largest ahu on Easter Island with 15 Moai, backs to the sea. The second one from the right wears a cylindrical red “pukao” on his head. Is it a hat, or does it represent a faddish hairstyle once worn by influential Rapa Nui males? Just one of the many Moai mysteries. (The red scoria stone used to carve the topknots was quarried at Puna Pau, 12 miles from the site where the heads and bodies were made.) Ahu Tongariki is the place to be at sunrise.

We crawled through lava tubes and caves. We admired the vistas at Rano Kau, an extinct volcano and crater lake. We posed for goofy pictures at Ahu Akivi, where the seven Moai stand who represent the seven original Polynesian explorers to Rapa Nui, led by Hotu Matua. (So they say.) We paid a visit to the Ahu Nau Nau Moai at Anakena, Rapa Nui’s only sandy, white coral beach.

We learned about the intense Birdman contest (follow the link to read about this, and join me in wondering why this is not a reality competition show RIGHT NOW). We wandered around Orongo Village, a network of clever semiunderground homes, where the competitors prepared for the race past Motu Iti to Motu Nui where they would grab sooty tern eggs and swim back through the waves with the prized eggs protected in little headband baskets.

We visited the strange and striking Iglesia Hanga Roa—Holy Cross Church—where carvings that decorate the sanctuary inside and out combine Rapa Nui and Christian symbols. At the church I remained on a bench in the garden to sketch the exterior while the rest of the group attended a short lecture inside. I got lost in the complicated drawing; when I finally looked up, to my horror, our tour bus was gone. The saints were with me though; I caught up with it down the street at the Artisan Market where later I’d buy a Moai souvenir carved from makoi wood.

The money shot of Easter Island is Rano Raraku, the quarry that supplied the stone for almost all of the Moai. Nearly 900 Moai are scattered about the site—many of the recognizable ones featured on postcards and seen on Instagram—including the 170 ton “El Gigante” who lies flat on his back, possibly abandoned during construction or intended to remain in eternal peace that way.

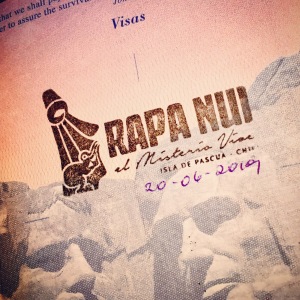

“Isla de Pascua”—Easter Island’s Spanish name—is part of Region de Valparaiso in Chile, and it was hard to keep up with the languages spoken there. One simple interaction could contain ia orana or maeva (hello and welcome in Tahitian), mesa para dos? (table for two in Spanish), ko ai to’u ‘injoa? (what is your name in Rapa Nui), and thank you, come again!

Even more confusing are the conflicting “facts” presented about the historical events of the island and the origin of the Rapa Nui people. Oral history and DNA and architectural and artifact clues all point in different directions, and the various theorists are generally adamant that their own interpretation is gospel. The official museum above Ahu Tahai houses interesting tools and artifacts as well as a video that discounted much of what our guide just told us in front of the Moai below, a half an hour earlier.

“The island was deforested to make log conveyances for the Moai, a cultural obsession, made worse by competitive clan wars.” Wrong: “the demise of the once-lush vegetation on Rapa Nui wasn’t ecocide, it was genocide, perpetrated by Europeans.” “The Moai weren’t rolled, they were ‘walked’ into various resting places on the island.” Or they were moved some other way; there are three top theories. “The Tongariki 15 were toppled during the island’s civil wars” versus “No, they weren’t, they were gently ‘put to sleep’, carefully lowered with ropes, face down.” Do not get anyone started on what the red pukao on the Moai heads represent, or incite the neverending debate about where the Rapa Nui people originated. Ahu Vinapu reflects Incan architecture; Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon Tiki expedition concurs: they came from South America. Or did they sail Northwest from Polynesian islands? Modern anthropologists are sure they are Marquesan—until someone else digs up a different story. Rapa Nui is the most most isolated inhabited nation in the world, and it’s bizarre there were—are—people there at all.

After a farewell dinner at the Eco Lodge, we transferred back to the airport for a midnight flight back to the InterContinental Tahiti Resort to await the Cruise to Totality.

Photos below:

Arrival on Rapa Nui; passport stamp

Hotel Hanga Roa Eco Village

Tahai

Ahu Tongariki; Puna Pau topknot

Ahu Akivi

Ahu Nau-Nau Moai and Anakena Beach

The Birdman; Orongo Village; Birdman motus

Iglesia Hanga Roa; Artisan market

Rano Raraku

Cliff by cave; wild guava; post office; local beer; boats at the marina